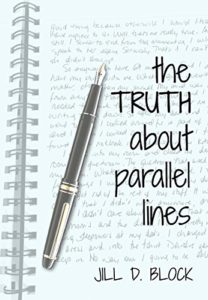

A few years ago, I attended an open-house/info session for an MFA writing program. At that point, I had written three stories, one of which turned out to be the beginning of what would become The Truth About Parallel Lines. My first story had been published about six months earlier, in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine’s First Stories Department. Although I had no personal interest in the program, I’d agreed to accompany a friend who was thinking of applying. They explained that the application would include an essay about the role that writing has played in the candidate’s life, or something like that. However they described it, my immediate thought was that if I were to apply my essay would be about the role NOT writing played in my life. I had spent my entire adulthood not writing. I had literally made a career of it.

A few years ago, I attended an open-house/info session for an MFA writing program. At that point, I had written three stories, one of which turned out to be the beginning of what would become The Truth About Parallel Lines. My first story had been published about six months earlier, in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine’s First Stories Department. Although I had no personal interest in the program, I’d agreed to accompany a friend who was thinking of applying. They explained that the application would include an essay about the role that writing has played in the candidate’s life, or something like that. However they described it, my immediate thought was that if I were to apply my essay would be about the role NOT writing played in my life. I had spent my entire adulthood not writing. I had literally made a career of it.

The first fiction I ever wrote was for a class my senior year in high school. For my final project, I wrote an original short story. It was easy, fun. The words poured out of me. It was the story of a girl, a high school senior, on a car trip with her father, what she called a get-to-know-your-daughter trip. The reader was privy to the conversation between father and daughter, and also to the girl’s unspoken thoughts. It was honest, and funny, and angry, and maybe a little sad. My teacher loved it, and gave me an A. I was so proud; I showed it to everyone. Except my father. The writer.

In college, I took a creative writing class at The College of the Holy Cross. (My school was part of a consortium with other area colleges, and Clark didn’t offer any creative writing classes that semester.) I wrote a few stories for the class, but it was hard, punishing. The stories didn’t come easily, and they weren’t good. At that point, I could write a research paper for a History class without breaking a sweat, but my efforts at writing fiction started to feel like I was carrying large and heavy things across a great distance. Maybe I was distracted by all that Catholicism. Just walking onto the Holy Cross campus made me feel exposed, slutty, like I didn’t belong and like I needed to hide who I really was. Whatever. My heart just wasn’t in it. I was done.

Two years later I sent the story to my father. I can’t remember exactly what made me decide to do so. In any event, he didn’t die. He didn’t even cry. (Or if he did, he kept it to himself.) He told me that it was good, and I believed him. He said that I should write some more. I didn’t. Instead, I applied to law school, thus ending my creative writing career. Or so I thought.

Thirty-one years later, my father invited me to write a short story for an anthology he was editing. That story, Like it Never Happened, ended up being published in Ellery Queen, so he asked me to write another for the anthology. I did, and The Lady Upstairs was included in Dark City Lights, and later republished in an Australian magazine. Since then, I’ve written four more stories and a novel.

I don’t have a copy of the story about the girl and her father. I wonder if my father does.